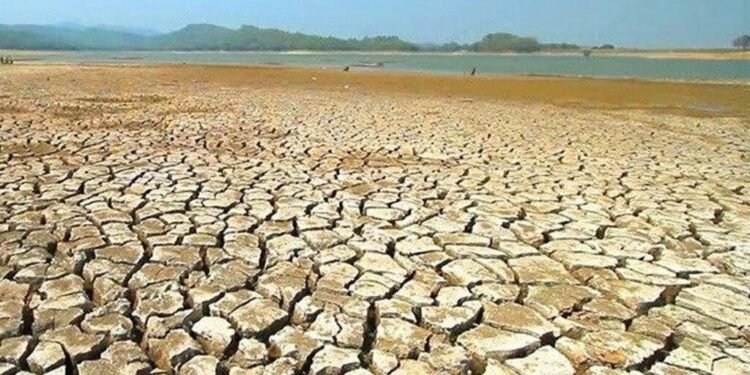

TEHRAN, Iran: Iran is facing one of its most severe environmental emergencies in decades, as water shortages threaten to make its capital, Tehran, home to more than 10 million people — virtually uninhabitable. President Masoud Pezeshkian warned this week that without rainfall by December, the government may have no choice but to ration water or even evacuate parts of Tehran.

“Even if we ration and it still does not rain, then we will have no water at all,” Pezeshkian said. “Citizens may have to evacuate Tehran.”

For many Iranians, this crisis is a chilling déjà vu. Past droughts have already fueled protests notably in Khuzestan province in 2021, when demonstrations over water shortages turned violent. But this time, the crisis is broader, deeper, and potentially destabilizing for a country already strained by sanctions and economic turmoil.

A Crisis Decades in the Making

Iran’s drought is not only about climate change or declining rainfall. Experts say it is the result of decades of mismanagement, overbuilding of dams, illegal wells, and wasteful agricultural practices that have drained rivers and aquifers.

According to Mohammadreza Kavianpour, head of Iran’s Water Research Institute, last year’s rainfall was 40% below the 57-year national average, and forecasts predict continued dry conditions through December.

Tehran’s five main reservoirs once capable of storing nearly 500 million cubic meters now hold barely half that capacity, with one major dam, Amir Kabir, at only 8% full.

“At the current rate of consumption, Tehran could run out of usable water within weeks,” warned Behzad Parsa, head of the city’s Regional Water Company.

Everyday Life Grinds to a Drip

In many neighborhoods, water pressure is reduced nightly, sometimes dropping to zero. Families wake up to dry taps and rely on bottled water or small tanks.

“It was 10 p.m. and suddenly the taps went dry,” said Mahnaz, a mother of two in east Tehran. “We had no water until morning. We brushed our teeth with bottled water.”

Authorities have denied formal rationing but acknowledge pressure reductions to conserve what remains. Meanwhile, millions are facing electricity and gas shortages too a triple crisis that has left citizens exhausted and angry.

“It’s one hardship after another,” said Shahla, a schoolteacher. “No water, no power, no relief. This isn’t nature’s fault it’s mismanagement.”

National Impact and Growing Anger

The water emergency extends far beyond the capital. Nineteen major dams across Iran — about 10% of total capacity have effectively run dry. In Mashhad, the country’s second-largest city, reserves have fallen below 3%, crippling small businesses and public services.

“The pressure is so low we can’t even operate our carpet cleaning machines,” said Reza, a business owner in Mashhad. “It’s completely due to government mismanagement.”

Environmental experts warn that climate change is accelerating Iran’s water loss. Rising temperatures are causing record evaporation, shrinking lakes like Urmia and threatening agriculture in fertile provinces once known as the country’s “breadbasket.”

Faith and Futility

Desperation is now driving both technical and spiritual appeals. Tehran’s city council chief Mehdi Chamran publicly suggested reviving the old tradition of “rain prayers” in the desert, as citizens look to divine help where policy has failed.

The government, meanwhile, has announced temporary transfers of water from other regions and is urging citizens to install pumps and storage tanks. Critics, however, say these are “band-aid solutions” for a structural collapse decades in the making.

“Too little, too late,” said a university professor from Isfahan. “They make promises every year, but the taps keep running dry.”

Iran’s water crisis is no longer an environmental issue it is becoming a national security threat. As climate stress intersects with political tension, Tehran’s dry taps may soon symbolize something larger: a government’s inability to manage the essentials of life itself.

-Alison Williams